So, I got to see Cecil Taylor again.

It took a bit of doing, schedule-wise, but I couldn’t turn down the opportunity to see a rare Cecil concert last month during one of my infrequent trips to New York. Missing it would have bothered me for years, even though I’d seen him once already — at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco.

That concert predates this blog. The gist was: Big, big church, but the resonating of the notes didn’t play into the sound as much as you’d think. Cecil was so busy that he’d overrun the reverberations quickly.

The Harlem Stage Gatehouse is a smaller venue, a little more intimate (and I left town before his show at Brooklyn’s Issue Project Room, an even smaller venue). It was packed, although there were enough no-shows for at least two people on the waiting list to get in. (Those two were my parents, who were coincidentally in New York and figured they’d try something different.)

Plenty of musicians were there. I sat next to Vijay Iyer, in the rearmost of three folding-chair rows arranged behind Cecil. I can’t believe those seats didn’t fill immediately. Elsewhere in the crowd, Craig Taborn was around; Butch Morris had a reserved seat. Nate Chinen of The New York Times had a reserved seat as well; he didn’t show up until the last minute and disappeared right after the final note. (Given the detail in his writeup, he must have been backstage with the organizers either before or after the show, fleshing out the finer points of the show.)

The show started with an audio collection of musicians explaining Cecil’s influence on them, on jazz, on music. It was a very nice tribute. (And Iyer was in it.)

Then, as he did at Grace Cathedral, Cecil opened by reciting poetry from backstage into a microphone. His words, like his music, tumble from seemingly everywhere, threading together nonsensically. There may be a theme, a path, but it’s incomprehensible to me. And yet, like his music, his poetry can’t be replicated by just doing things randomly. Grabbing fistfuls of scientific and astronomical terms and stringing them together like popcorn will not produce the sound, rhythms, and music of a Cecil Taylor poem.

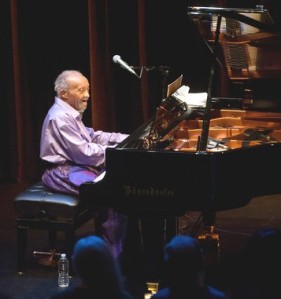

Being 83, Cecil looks and sounds old. His voice is gruff and short-breathed, and his gait is hobbled, just the usual effect of being 83. So, he approached the piano slowly and took his time shuffling through his scores. I couldn’t see clearly enough, but it wasn’t sheet music — it looked like vertical columns of symbols, like Asian writing or sloppy note designations. I could be wrong, but that’s the shape I kind of made out from my seat.

There were four or five pieces, I think, each ending with a long pause as Cecil thumbed through the scores again to pick the next target. No one applauded between pieces — we should have, but pieces ended abruptly, and it was hard to tell if Cecil was done or simply transitioning between movements.

After two pieces, in fact, he seemed to feel the awkward weight of the air. So, he stood up and read a second poem, recited with punch and even some humor. This was the one Chinen cites that included the line “effluvium and effluvium” followed by six or seven more “effluviums” — and we laughed, as I’m quite sure Cecil had hoped we would. That finally broke the ice. Cecil went back to work in the keyboard with a renewed vigor.

He took two encores, the second almost at the insistence of the festival organizers (this was his festival, after all!) Both encores were short — Cecil does know how to work with an audience’s patience — and the second was in a head/solo/head format! Yes, Cecil overtly played something twice! The head was a sneaky chromatic left-hand line with right-hand splashes, very melodic and a litle bit sassy, with a touch of (oh no) tonal resolution. It was still “out there” but not like anything he’d played so far in the concert. He ended it tonally too (i.e., it sounded like a quiet, graceful ending). A real treat.

Cecil got rousing ovations for his work that night, and why not. Aside from being masterful in the first place — my parents aren’t free-jazz fans, but they found his piano abilities stunning — this was a chance to openly thank a man who created entire new generations of music. You could argue that with these solo concerts, Cecil is coasting — but if he is, 1) he’s earned it and 2) there are still plenty of us around who didn’t see him dozens of times over the decades. There’s an audience.

As for the bulk of the music itself, the specifics are mostly worn away in memory. It was Cecil. Lots of tumbling runs; flickering chords that felt like they were creating new harmonies never before discovered, but only for a second before being erased by the next event; the occasional forearm slap to the keyboard. He still tells the tales in a way that only Cecil Taylor can.

Other resources:

- Nate Chinen’s NYT writeup

- Burning Ambulance #5 — includes Phil Freeman’s analysis of Cecil Taylor’s 1980s albums.